27. January 2026 By David D'Alessandro

The psychology behind social engineering

Some cyber attacks are not only carried out by hackers with a purely technical focus, but also by people who exploit the subconscious to manipulate you. In this blog post, I will therefore show you how social engineering works and why our brain is the biggest security vulnerability.

The danger: What is social engineering?

According to the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI), social engineering is one of the most significant threats to IT security. Attackers use this method to bypass technical security measures via employees and gain access to the company network. They use various manipulation techniques via different attack vectors (email, telephone, direct contact) to achieve their goals.

However, although the BSI calls for targeted training to ensure sufficient security awareness in module ORP.3, many approaches remain too superficial. Some training courses merely offer technical ‘checklists’ for phishing emails and ignore the psychological complexity of attacks via LinkedIn, telephone or direct contact. We need to rethink our approach and also take socio-psychological factors into account in training programmes. However, security awareness is not everything. Our current meta-study addresses other topics in the field of IT security. In the following, I will explain the mechanisms behind social engineering.

Security awareness

Raising awareness of cyber security

In a digitalised world, technical protective measures alone are not enough. Cyber attacks increasingly exploit human vulnerabilities, whether through social engineering, phishing or manipulated communication. With adesso, you can establish a security culture that goes far beyond mandatory training – for greater resilience, fewer security incidents and stronger overall information security.

The reasons: Why do we fall for social engineering?

At this point, I would like to be able to tell you which personality traits, thought patterns or work situations make people more susceptible to social engineering. Unfortunately, there are currently various explanatory models for susceptibility, none of which have been reliably validated and recognised.

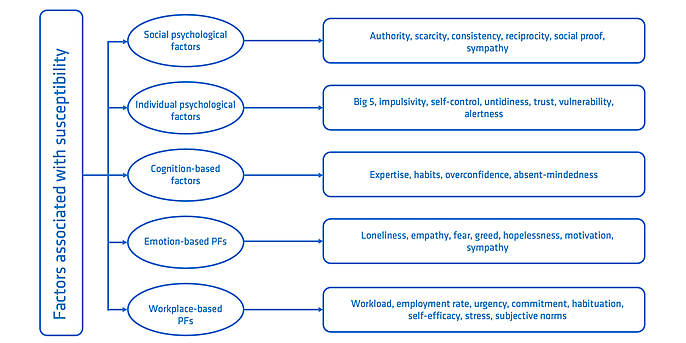

Figure 1 is based on the grouped personality factors identified by Longtchi et al. (2024) in Figure 3 of their paper: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2024.3379855. The figure shows five groups of different psychological factors that could influence susceptibility to social engineering.

Figure 1 shows a comprehensive, albeit incomplete, summary of potential factors compiled by Longtchi et al. in 2024. Some of these factors have been examined in more detail, revealing plausible correlations in some cases. However, for some factors, the situation is unclear due to conflicting findings. Therefore, my remarks will be limited to some of the socio-psychological factors for which reliable findings already exist.

a. Conscious and unconscious information processing

Before I explain the socio-psychological factors to you, it is important to know that our brain uses two ways to process social situations.

- The first way is fast and intuitive. In this way, processing is unconscious, emotion-driven and enables quick decision-making. Rules of thumb are applied that have been ingrained in us through social conditioning. An example of such a rule is the principle of social proof (‘If everyone is doing something, then it must be good.’). The use of such a mental shortcut prevented social exclusion from the herd, at least in primitive times, and ensured survival.

- The second way is slow and rational. Compared to unconscious processing, this process is active. We think about a situation for a longer period of time before we act. The decision is more thoughtful, takes several factors into account and usually distances itself from simple solutions.

In everyday life, subconscious rules help us, for example when we rely on Google reviews and thus on ‘social proof’ when choosing a restaurant. These rules only become problematic when situations are more complex and require well-thought-out solutions. One example is choosing an app based solely on the number of downloads. Just because millions of people have downloaded Google Authenticator doesn't mean you should too.

With regard to social engineering, research shows that victims react more vulnerably when the situation is treated casually. Suspicion of social engineering occurs more frequently when it is consciously processed. The insidious thing about this, however, is that attackers use their techniques to try to trigger the rules of thumb we have learned and also want to keep us in subconscious processing by emotionally charging us. They achieve this by triggering time pressure, fears, sympathies, resistance or anger. To escape this state, we must switch to conscious processing and learn to recognise attempts at manipulation. That's why I'd like to explain the two most common manipulation techniques so that you can recognise them in future.

Meta study

Security reimagined

Our meta study provides a concise overview of the risks companies face today and how they can ensure the security and competitiveness of their business despite increasing complexity. The focus is on holistic security strategies ranging from governance, risk and compliance to secure IT/OT architectures, rapid threat detection and resilient processes to the secure use of new technologies.

b. Manipulation techniques used by perpetrators

Scientific studies on social engineering manipulation techniques are often based on Robert Cialdini's seven principles of persuasion. He derived these principles from the field of psychology and explained them in his book ‘Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion’. In it, he describes how they can be used as tools, recognised and defended against. In my remarks, I will limit myself to the use of these principles in phishing emails, as this is where the principle of authority and the principle of social proof are most frequently used. However, they can also be applied to other attack media (such as LinkedIn).

Authority

Cialdini derives the principle of authority from the Milgram experiment. In this study, participants were instructed by the experimenter to harm another person, even though this contradicted their personal beliefs. The main finding is that around 60 percent of participants obeyed the command even when it meant harming others.

This tendency is based on the social perception that people with a certain rank have a lot of experience and know the ‘right’ way to do things. Unfortunately, simple symbols (clothing, titles) are enough for us to perceive people as authorities or experts. In a work context, titles such as CEO, Doctor or Senior can convey an impression of authority. Attackers exploit this fact and write emails in the name of high-ranking individuals. This form of fraud is known as CEO fraud.

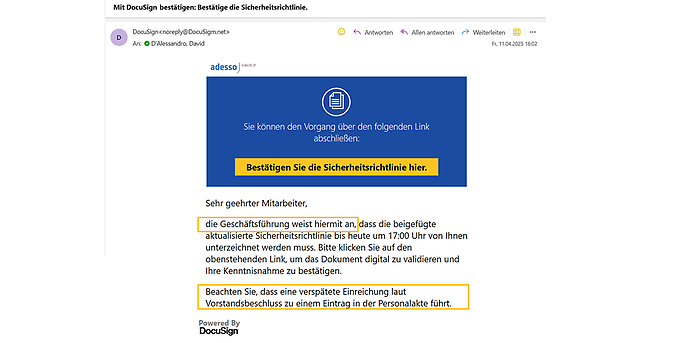

Figure 2: Authority-based phishing email

In Figure 2, the attacker asks the recipient to click on a link on behalf of the management. In a so-called drive-by attack, this click is enough to download malicious code and compromise the computer. However, CEO fraud does not necessarily have to take the form of a drive-by attack. Sometimes it is enough for the attackers if employees disclose company data or transfer money.

The best way to avoid CEO fraud is to question the person's expertise or professional competence and the veracity of their statements. Is the decision on the intranet? Has my manager heard about it? This technique distracts attention from symbols such as titles and weakens trust in the person. Also, don't let yourself be pressured, even if you are given a sense of urgency. Unfortunately, attackers rely on a combination of manipulation techniques. Among other things, they create pressure by artificially limiting the time available for a decision. In such a case, it is better to play it safe than to be unable to work for several days due to a compromised computer. If you need assistance in evaluating an email, contact the relevant security department.

Social proof

Another manipulation technique is based on the principle of social proof. It was derived from the famous Asch experiment. In this experiment, test subjects compared the length of lines. Although the answer to the question was clear, 75 per cent of the subjects agreed with the (deliberately incorrect) opinion of a group. This tendency is based on our need to belong and the belief that a large group has more information than we do.

This subconscious mechanism occurs when we find ourselves in an unclear situation, and it is reinforced when we resemble the comparison group. Attackers exploit this by pretending that a large number of colleagues have already performed a certain action, thus conveying a false sense of security.

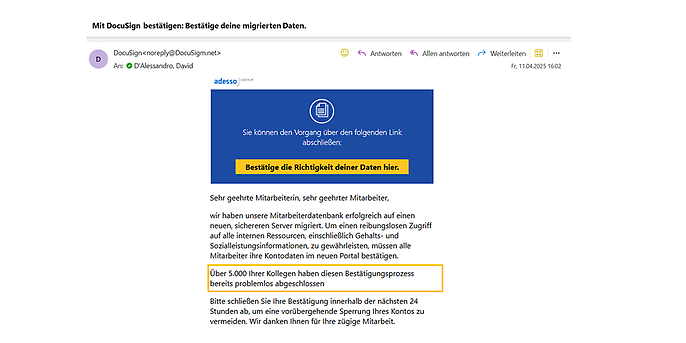

Figure 3: Phishing email refers to social proof

In the third image, you can see how attackers refer to the fact that a large number of colleagues have responded to an urgent request in the example email. This puts pressure on the recipient and makes them feel like they are the odd one out. It is worth noting that such attacks do not only take place via email. This method is also used in a similar way on social networks. Phishing links are distributed via fake posts, their likes are driven up by bots, and sometimes colleagues' profiles are hijacked to increase credibility through sharing.

The best way to escape the influence of social proof is to recognise that this effect exists and that it influences you, albeit minimally. As with authority-based attacks, it is also helpful to critically examine the statements. Question whether the figures quoted are plausible or whether there is official information on the intranet that confirms a statement. When in doubt, it is better to check with the security department once too often than to blindly follow a fake majority.

Conclusion – What you should learn from this

Social engineering exploits the weaknesses of subconscious information processing. Instead of looking for technical gaps, attackers use socially established rules of thumb against us.

The most common form is CEO fraud, in which the status of an authority figure is abused. Attackers use status symbols to force our obedience, as people tend to question their superiors less often. Other techniques make use of social proof and the associated peer pressure to reduce a person's inhibitions.

For self-protection, it is important to switch to active information processing. Recognising manipulation is the first step. Subsequently, healthy scepticism can mitigate social pressure by questioning either the authority or the group. If necessary, take the time to ask a colleague – you are not alone in the company.

We support you!

adesso helps you to establish a culture of security together with your employees and to create sustainable resilience against cyber attacks.